CODING PLANTS

An Artificial Reef and Living Kelp Archive

La Biennale di Venezia Architettura, 19th International Architecture Exhibition: Intelligens. Natural. Artificial. Collective.

Growing an Epigenetic Reef and Botanical Memory System

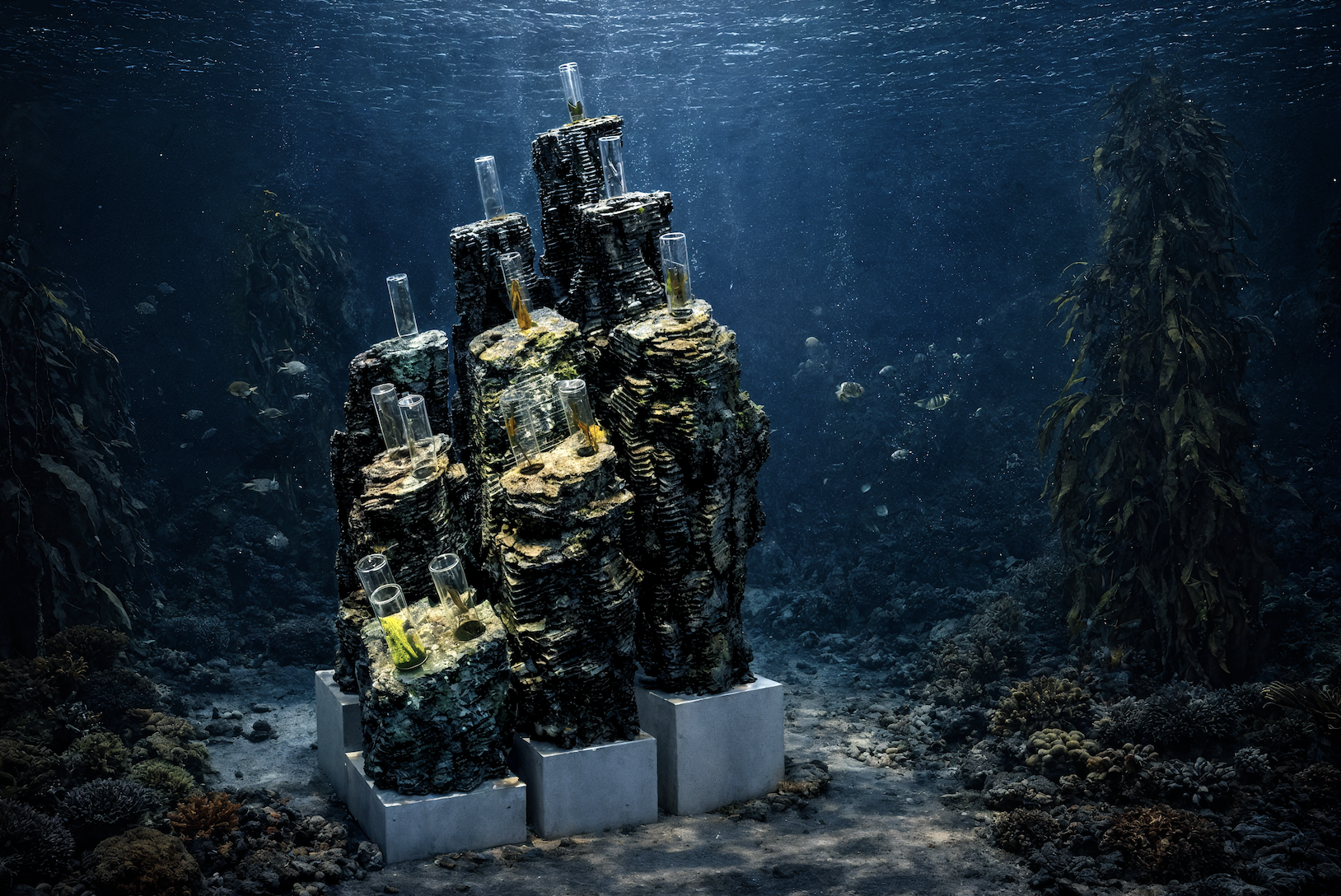

This is a neo-natural kelp reef where architectural records are transformed into edible proteins. Encased in air-tight vitrines, a collection of suspended, dried seaweed specimens showcases a transgenic process. Scientists have embedded encoded information—texts, images, and drawings—directly into the genetic material of this engineered vegetation, effectively turning the reef into a living, edible library. The 3D model at the center of the reef physically represents the phrase Form Follows Function, ciphered in the AGTC sequence of DNA. At the planetary scale, the system unites two powerful sinks: carbon sequestration and cold data storage.

The title Coding Plants reflects our vision of embedding digital information into living systems to transform how we design and build. A single gram of plant DNA can theoretically store up to 215 million gigabytes of data. The project articulates a dual premise: the encoding of semantic and spatial information within botanical systems, and the broader implication of living matter as programmable infrastructure. While kelp is technically a macroalgae, not a plant, we use the term “plants” broadly—referring both to botanical life and to systems of production, as in “manufacturing plants.” Kelp serves as our transgenic prototype due to its ecological value and its potential for DNA-based data storage. The name signals a future in which living organisms—plant or otherwise—become computational, functional elements of architecture.

In the future, libraries won’t be built, but grown. Botanical organisms will be genetically augmented to store the knowledge of specific architectural forms—houses, bridges, communal spaces, and more—that can be extracted and used to challenge polluting construction methods. The goal is to design urban environments that adapt and evolve in balance with their surrounding metabolism. Plants will function as living archives, encoding detailed information within their DNA, allowing users to guide and influence their growth and structural form. This approach integrates radical sustainability directly into a semi-natural ecosystem, creating a harmonious blend of hybrid nature and human innovation.

Coding Plants is a synthetic living reef that serves as the ultimate archive of design knowledge. By embedding complex architectural intelligence into live organisms, Coding Plants proposes a climate positive agenda in which nature is empowered at the genetic level. While this vision may appear speculative, it is grounded in recent breakthroughs in genetic engineering. This approach heralds a fertile architecture that reimagines conventional building practices while fostering resilience, adaptability, and ecosystem integration. READ MORE

Earth Ocean

-> PLAY Sound Composition by Paul D. Miller aka DJ Spooky

Every forest is a symphony. Polyphony. Polyrhythm. Ultra dense canopies of sound. The acoustic call and response of every species in the ecosystem creates a complex acoustic architecture that fosters a dense and hyper layered phenomena that follows the totality of the way we think of any forest. The complex sound systems that animate forests are an incredibly rich tapestry. But what happens when we look at the way sound and plants act underwater? What happens when we look at the interplay of biophonic architecture as a kind of pattern recognition based on acoustic phenomena?

Kelp forests are often called “rainforests of the ocean” because they are a reflection of complex underwater ecosystems that provide food and shelter for many species. Kelp are large brown seaweeds (phaeophyta), in over 30 different genera that live in dense clusters in the cool waters close to the shore. Amazingly enough, kelp forests are one of the most widely distributed marine primary producers that remove and sequester some amount of CO2 from the atmosphere. The amount will vary from place to place and over time, but the basic idea is that they are a super important part of the global ecosystem. According to several studies, kelp forests provide around $500 billion in value to global commerce and capture, at a minimum, over 4.5 million tons of carbon dioxide from seawater each year. Most of kelp’s economic benefits come from creating habitat for fish and by sequestering nitrogen and phosphorus – the amount of greenhouse gases sequestered depends on which location and which species of kelp we are looking at, but the general idea is that they are a critical component of the way we think of some of the largest phenomena on Earth – the oceans and their relationship to the carbon and oxygen cycle that animates the planet.

The history of Western music has a couple of major compositions that focus on water: Handel’s “Water Music,” John Luther Adams “Become Ocean,” David Tudor’s “Rainforest,” Ravel’s “Jeux d’eau,” John Cage’s “Water Music,” Debussy’s “Le Mer” … the list goes on. The basic idea is that composers have engaged the concept of water songs to celebrate the fact that water is the core of life and it’s relationship to the core aspects of what makes Nature so powerful. On the other hand, kelp is a bit more under the radar. How many of us can name songs after one of the most important plant species of the ocean?

What scientists call “biophony” is the sound of the biosphere as humans have interpreted it. In this situation, sound is an artifact of deep time. Think of the genome of algae and kelp as a dataset, and a component of computational biology. Plants colonized the land as they moved from the oceans to dominate the terrestrial environment around 500 million years ago during what scientists call the Ordovician period. We live in the deep time accumulated, nonlinear world of the law of unintended consequences and genetic selective adaptation, and every plant around you shows the etching of deep time in a mega cycle of evolution. The evolutionary impact of this transition of the movement of plants onto land was a significant step in Earth’s history, as it eventually allowed for the development of terrestrial ecosystems and the emergence of land animals. Every garden, every farm, every forest and meadow – they all owe their existence to this migration in deep time. The case for the composition I am making is based on how music is an abstract machine composed of many moving parts. The basic idea would be a data sonification of the genome of algae and its generative models. READ MORE

_______________________________________

Credits: Terreform ONE

Mitchell Joachim, Peder Anker, Melanie Fessel, Paul D. Miller, aka DJ Spooky.

Studio: Vivian Kuan (Executive Director), Julie Bleha.

Design: David Paraschiv, Emily Young, Sky Achitoff, Avantika Velho, JJ Zhijie Jin.

Science: Oliver Medvedik, Sebastian Cocioba.

Collaborators: Wendy W. Fok, WE-DESIGNS.

Media: Michelle Alves de Lima.

Structural Engineer: Justin Den Herder, PE, (Principal), TYLin, Robert Silman Associates Structural Engineers.

Research: Marina Ongaro, Ava Hudson, Nicholas Lynch, Jerzelle Lim, Helen Gui.

Sponsors: U.S. National Endowment for the Arts, New York University, NYU Global Research Initiatives in the Office of the Provost, Oslo School of Architecture and Design, RheinMain University of Applied Sciences.

Special Thanks:

Carlo Ratti, Curator of the 19th International Architecture Exhibition. Victoria Rosner, Dean of Gallatin School of Individualized Study at New York University.

Video: 3D model of an artificial epigenetic reef and underwater memory system. A design for living organisms to become computational, functional elements of architecture.